The Game of Monopoly: Is it Child’s Play or a Roll of the Dice for Big Business?

The official history of Monopoly, as told by Hasbro, which owns the brand, states that the board game was invented in 1933 by an unemployed steam radiator repairman and part-time dog walker from Philadelphia named Charles Darrow.

The game’s true origins, however, go unmentioned in the official literature. In 1903, three decades before Darrow’s patent, a Maryland actress named Lizzie Magie created a proto-Monopoly as a tool for teaching the philosophy of Henry George, a nineteenth-century writer who had popularized the notion that no single person could claim to “own” land.

Magie called her invention The Landlord’s Game, and it looked remarkably similar to what we know today as Monopoly. The Landlord Game’s chief entertainment was the same as in Monopoly: competitors were to be saddled with debt and ultimately reduced to financial ruin, and only one person would stand tall in the end.

In both games, the objective is to have just enough so that everybody else has nothing. In this view, a monopoly is not about unleashing creativity and innovation among many competing parties, nor is it about opening markets and expanding trade or creating wealth through hard work. It’s about shutting down the marketplace.

I can remember playing Monopoly for hours and hours as a young boy. I must confess I didn’t connect the dots on what a monopoly was until much later in life, and I never imagined that I would be investing in real estate as a career. As it turns out, one of the secrets to building wealth really is four green houses and one red hotel.

The definition of a monopoly is “the exclusive possession or control of the supply or trade in a commodity or service.” The key word is exclusive — so exclusive that they have such effective control of their market that they can set prices and stifle innovation by depriving competition of any chance of profit.

Perhaps a modern lesson on monopolies can be drawn from the breakup of American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) in 1983. The government had actually protected AT&T’s market domination during the first half of the 20th century because of AT&T’s commitment to make telephone service universally available in the United States. However, by the 1980s, many critics argued that the company was so large and monopolistic that competition had been stifled and consumers were being deprived of choice in the long-distance telephone market. In response, the courts forced a breakup of the company into seven regionally-based “Baby Bells” (Southwest Bell, Southern Bell, etc.).

“The definition of a monopoly is “the exclusive possession or control of the supply or trade in a commodity or service.” The key word is exclusive”

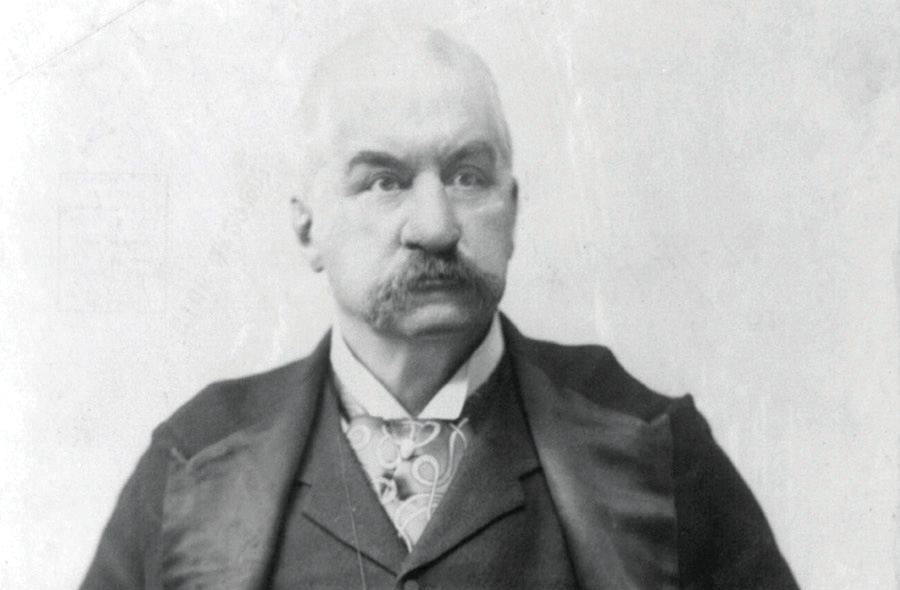

If you “Google” names from the late 1800s in the era of powerful trusts controlled by men like Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan, you will find that big business was all about forming a monopoly. So it’s no surprise that the game Monopoly was founded on what was happening at that time. The board game has some amazing similarities to the game of business titans have played over the years.

According to Phil Orbanes, former Vice President of Parker Brothers, the original owner of Monopoly, Rich Uncle Pennybags of the American version of the game is modeled after J. P. Morgan. This is hard to dispute when you compare his picture to the actual character. His namesake company he helped form, J.P. Morgan, reportedly bailed out the U.S. Treasury in 1895 and again in 1907, before helping to create the Federal Reserve System in 1914.

In rule number11 of the game of Monopoly, the “banker” can never go bankrupt and can “issue” new money on ordinary slips of paper. It’s clear that rule number 11 was based on the banking practices of the early 1900s and these same practices continue today. The monetary policy of the Federal Reserve System is based partially on the theory that it is best overall to expand or contract the money supply as economic conditions change. If you understand this point, you can then be on the right side of the expansion or contraction.

I never paid much attention to the utility and railroad companies between the properties in the game Monopoly; they always seemed like an annoyance if I landed on them. What’s interesting is that J.P. Morgan also bailed out and combined bankrupt railroads and utility companies, stacked their boards and “stabilized” rates before these were the first to be “busted” by the Sherman Anti-Trust Act.

In 1885, J.P. Morgan brokered a trust between two rival railroad firms, the Pennsylvania Railroad and New York Central, ending their rate wars, and he financed or refinanced several other competitors, including two you’ll recognize from Monopoly: the Baltimore & Ohio and the Reading Railroad. With Morgan’s control of the boards of these companies, competition was very friendly and profits very large.

For years, Morgan was the primary investor in Thomas Edison’s projects. In 1892, Morgan arranged the merger of Edison General Electric Company with the Thompson-Houston Company to become General Electric, which, with competition again eliminated, became wildly profitable.

Additionally, Morgan had begun talks with Charles M. Schwab, president of Carnegie Co., and businessman Andrew Carnegie in 1900. The goal was to buy out Carnegie’s steel business and merge it with several other steel, coal, mining and shipping firms to create the United States Steel Corporation. In 1901, U.S. Steel was the first billion-dollar company in the world.

What a fabulous time to be alive. There really is so much more to the story, and the History channel did a great job producing a series about it called “The Men Who Built America.” Be sure to catch it.

In looking at a list of potential monopolies that exist today, people may be surprised to learn that all of the companies on the list are technology based. Industries which are large but only recently established are often controlled by just one company. That was true when the PC was introduced widely in 1980. Microsoft offered the only PC operating system that had enough market share to make it viable. That dominance fed on itself as the number of PC manufacturers and users rose.

In our lifetimes, the Internet has created another “land grab” of opportunity, just like in the Industrial Age. We are living in a time of huge opportunity and potential abundance, just like in the History channel’s documentary.

The best is yet to come. The world will always be full of those that will disagree with me. I still remember finding humor when reading about Mr. Charles H. Duell, the Commissioner of the U.S. Patent Office in 1899, and his famous utterance that “everything that can be invented has been invented.”

In today’s world, you have to teach yourself how to be something more. The purpose of the education system today is to produce good workers. Most people are rewarded for subordination, unlike their superiors, who, of course, have their own rules. Andrew Carnegie said it best: “The greatest astonishment of my life was the discovery that the man who does the work is not the man who gets rich.”

“In looking at a list of potential monopolies that exist today, people may be surprised to learn that all of the companies on the list are technology based.”

I continue to tell my kids: respect your teachers, but understand that there is no single clear path to success, including college, and that the people in charge do not necessarily have all the answers. Your learning begins when you leave the classroom. Blaze your own path and create a career that solves a need for the world.