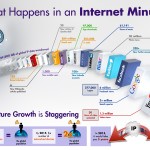

In one minute (roughly the time it will take you to read this paragraph) online: 204 million emails are sent, 20 million photos are viewed, 2+ million searches are conducted on Google, 1.3 million videos are viewed on YouTube and 100,000 new tweets are sent.

And this incomprehensible activity is projected to expand exponentially as the number of connected devices grows to double that of the world’s population by 2015. With this rapid expansion in connectivity comes another growth of even greater ferocity – the mass and value of your personal data. The truth is, behind the glossy exterior of some of our favorite online platforms and points of sale, an increasingly large body of data is being collected and refined to create our digital profiles. And the hidden cost of our “free” online interactions is being paid elsewhere, where our data is mined and studied often in order to create highly-targeted advertising or other profit-generating activities.

All of the interactions in your connected life leave a personal trail of data that is both increasingly revealing and, to some, remarkably valuable. We are constantly clicking Like, Share, Comment, Bid, Buy, Rate, Recommend, but we rarely give thought to where that wealth of data goes, or how it is being used by the services on which we pour out our digital souls.

An entire industry is profiting wildly on the market for your data. Massive data brokerage companies like Acxiom and T-Sys are just two of hundreds of enterprises who are peering into your personal life, collecting data that is generated from everything you do online and much of what you do in the real world. And by generating billions in sales each year offering “analytical services” on nearly every household in the U.S., they are profiting from all that you do in the connected universe. Moreover, this is just a fraction of the evolving – some say loosely regulated – big-data industry now valued at over $300B a year and employing three million people in the United States alone, according to the McKinsey Global Institute.

Unlike the national Do Not Call List, which gives consumers a one-stop location to have their telephone numbers removed from telemarketing databases, personal data collection and marketing does not have a universal opt-out system. So here are five things to consider when thinking about the protection of your online data:

- First, Value Your Data. Most of us would consider our cars one of our more prized possessions. We care for them, insure them and protect them from harm. Now think, as of this writing, the combined market capitalization of the world’s three leading auto manufacturers – General Motors, Volkswagen, and Toyota – is an astonishing $287B. By comparison, however, it’s revealing that the combined market capitalization of Facebook, Google, and China’s search giant Baidu is over $350B. What is so remarkable about this comparison is that these Internet leaders achieve their results by selling the information collected from the data trail you leave when you use their services. We rarely stop to think about the value of our data, but many experts theorize that shortly we will be able to personally monetize our private data storehouse. If the capital markets value companies so highly for using your data, we should begin to consider its inherent value, as well.

- Follow The Money. Free, Really Isn’t. While it may seem too simplistic to consider the way a company makes money when thinking about your data, it is at the very core of the data privacy narrative. The most obvious test to determine the degree of personal data exploitation is the “implied business model” test. If you use a site for “free,” but it is littered with advertising, then it is highly likely that they are using your interactions with their content to increase advertising rates (advertisers will always pay more when they can more clearly determine the precise target of their ads). Examples of this practice are prevalent almost everywhere: the next time you check your free Hotmail or Gmail online, look to see if there are targeted advertisements alongside your webmail inbox, specific to the content of the private email you are reading.

- Police The Policy. Who owns your data? There are generally two kinds of services: one maintains user data privacy and profits from monthly or annual subscription fees. Another is “free” to use and profits from selling advertising. The latter is more likely to be an offender of proffering your personal data (preferences, contact details, behaviors). While there may be a blend of free and paid options, another means of discerning how a service will use your data is in their policy statement. When you sign up to use an online service, you are agreeing to an End User License Agreement that makes the rules by which you’re engaging with their service. In most cases, these agreements (or similar policy statements) will indicate the extent to which the company whose service you are using will use your data. So, first look at who owns your data. Some licenses will tell you that when you use their service you give them the right to do anything with both the data they collect about your site visit (where you click, how long you’re spending on each page you view, how many pages you view, how frequently you return, etc.) and the content you post on their site. But sometimes this distinction is not clear. Take Facebook, for example. While they make it clear that you own the data you post to their site (photos, videos, comments, and other posts), they also indicate that they can use that data in whatever way they please.

- Know Your Data’s Health And Whereabouts. Security technology must evolve just to stay ahead of those determined to break it; today’s assurances of data safety and privacy are tomorrow’s hacking targets. Trying to stay ahead of the nefarious digital worms, moles, e-parasites and the infinite varieties of denial-of-service attacks is the domain of highly-trained technologists whose role in the Internet eco-sphere is becoming more central. The average user cannot expect to evaluate the merits of the technology employed to protect their data. But, according to Trov’s Director of Privacy and Security, Jon DeBonis (former data security specialist at Google), if you’re curious about a company’s security technology, a good first step is to find out whether the data they collect is encrypted. Encryption renders the data unreadable even if there’s a way to get at it. High-level encryption is virtually unbreakable, however, it is costly to implement – both in terms of real dollars and compute cycles – so some companies skimp on the application of this critical technology. Another way is to find out where your data is stored. The physical location is indicative of the kind of thought they put into security. One data center operated by Switch Communications in Las Vegas has military-trained security armed with automatic weapons on hand 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to protect its sensitive information and server space – similar to how international defense forces secure diplomatic embassies.

- Cover Your Assets. Since data is a valuable asset, start to look for applications and online services that agree with that perspective. These companies will offer easy ways to collect and manage your data and help you benefit from it directly. You’ll be able to identify these applications and services because they’re not strewn with advertising, their privacy policy respects the value and personal nature of your data, they give you easy ways to view and profit from your data and they collect fees from subscriptions or other non-advertising-related subsidies. A few companies are setting down tent pegs in this area – providing data security with world-class services. E-memory archive service Evernote, online personal finance management software Mint, and most recently, the tangible wealth management platform Trov, are leading the way for those who want simple, powerful, high-utility user experiences with clear title on their data and top-drawer security. What marks these companies is the ease with which data is collected and made usefully accessible, their commitment to privacy and the alignment of their business objectives with the data usage and privacy concerns of their users.

Naturally, there is somewhat of a generational distinction at play here. Those under the age of 35 (or Millennials as they are sometimes referred to), don’t think of either privacy or security in the same way their parents do. Despite daily reports of data hacking, e-system breaches and Internet theft, this demographic continues to boldly lead society into a new world of personal disclosure and information sharing, the likes of which we’ve never seen. Add to this the fact that Millennials stand to inherit the greatest amount of wealth in history – an estimated USD $30T in the next two decades – and an interesting phenomenon begins to emerge. It may be the case that data privacy is a temporary tension that will be resolved as alternatives emerge. And emerge they will.

The increasingly volatile admixture of data exploitation and the value of personal information is fomenting a growing support for business visionaries, technologists, venture capitalists and even lawmakers to explore alternatives for collecting, controlling and profiting from personal data. New businesses, technologies, practices and laws will arise that will eventually challenge the dominance of popular models purporting to be “free.” Inevitably, these new models will give way to a triumph of individual ownership and personal profiteering from your data.

So, with the volumes of information crossing in the connected digital ether and the implications for the future of your data, the next time someone tells you that they need “all the information,” the right response might simply be, “just wait a minute.”