The virtue and value of individual equanimity has been extolled and advocated by wise thinkers and philosophers for centuries.

It represents a calm, tempered, even mind, or a state of psychological stability and composure. It has been one of the secrets of wisdom, achievement and longevity. Those with equanimity can remain undisturbed by outer perturbations or other phenomena that may cause others to lose the balance of their minds.

Just as within individuals, so, too, within personal or professional partnerships, equanimity (or its corollary equity) has been extolled for its power in creating sustainable relationships. Many theories of equity have emerged over the decades, but most have attempted to explain relational satisfaction, or fulfillment in terms of perceptions of fair/unfair distributions of resources within inter-personal or inter-professional relationships.

Relationship partners seek to maintain equanimity within themselves and equity between them and their partners or at least between the inputs that they bring to their relationship and the outcomes that they receive from it. They value fair exchange and they are driven consciously or unconsciously to keep this fairness maintained within their relationship. The structure of such equity is based on the ratio of inputs to outcomes, or cost and services to rewards. If either perceives themselves to be either under-rewarded or over-rewarded they will experience distress, and this distress will drive them to make efforts to restore equity within their relationship.

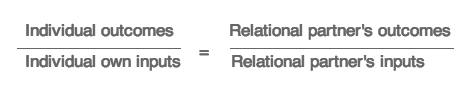

Equity is measured by comparing the ratios of contributions and benefits of each partner within the relationship. Relationship partners do not have to receive exactly equal benefits or make equal contributions, as long as the ratio between these benefits and contributions is perceived to be the same.

There are subtle and variable individual factors affecting each partner’s perception and assessment of their relationship with their partner. Anger is induced by under-reward inequity and guilt is induced with over-reward inequity.

In any personal or professional relationship, a partner wants to feel that their contributions are being compensated with equal rewards. If a partner feels under-rewarded, then it will result in the partner feeling hostile towards the other partner, which may result in the partner not functioning well in the relationship.

There are subtle variables that also play an important role in the feeling of equity. Just the idea of recognition and the mere act of thanking the partner will at times cause a feeling of satisfaction and therefore help the partner feel more worthwhile. This can result in a more equitable and sustainable outcome.

A partner will consider that he or she is treated fairly if they perceive the ratio of their inputs to their outcomes to be equivalent to those around them. Thus, all else being equal, it would be acceptable for a more intimate or meaningful relationship to receive a higher compensation, since the value of his or her relationship is higher. The way partners base their experience with satisfaction for their relationship is to make comparisons with themselves and others they see their partner interacts with. If a partner notices that another individual is getting more recognition and rewards for their contribution, even when both have done the same amount and quality of interactions, it would persuade the partner to be dissatisfied. This dissatisfaction would result in the partner feeling underappreciated. The idea is to have the rewards (outcomes) be directly related to the quality and quantity of the partner’s contributions (inputs or services). If both partners are perhaps rewarded the same, it would help the relationship to realize that the relationship is fair, sustainable and appreciative.

Relationship inputs are defined as each partner’s contributions to the relational exchange and are viewed as entitling him/her to rewards or costs. The inputs that a partner contributes to the relationship can be either assets – entitling him/her to rewards – or liabilities – entitling him/her to costs. The entitlement to rewards, or costs ascribed to each input, vary depending on the relational setting.

Outputs are defined as the positive and negative consequences that one partner perceives the other partner has incurred as a consequence of his/her relationship with them. When the ratio of inputs to outcomes is close, then the partner will have satisfaction with their relationship. Outputs can be both tangible and intangible.

As in marriage and other contractual dyadic relationships, equity assumes that partners seek to maintain an equitable ratio between the inputs they bring to the relationship and the outcomes they receive from it.

Partners in relationships have different preferences for equity and thus react differently to perceived equity and inequity. Preferences can be expressed on a continuum from preferences for extreme under-benefit to preferences for extreme over-benefit. Three basic forms emerge:

- Entitleds: Those who prefer their own input outcome ratios to exceed those of their relational partner. The entitled prefers to be over-benefitted and can be temporarily identified as a self-exaggerating narcissist. These partners feel they have been previously challenged by an unfair exchange or some form of under-benefit treatment.

- Equity Sensitives: Those who prefer their own input/outcome ratios to be equal to those of their relational partner, sometimes identified as fair exchangers.

- Benevolents: Those who prefer their own input/outcome ratios to be less than those of their relational partner. The benevolent prefers to be under-benefitted and can be temporarily identified as a self-minimizing altruist. These partners feel they have been previously supported by an unfair exchange or some form of over-benefit treatment.

An alternative measure of equity/inequity in relationships is when a partner judges the overall fairness of their relationship by comparing their inputs and outcomes with an externally-derived standard (injected social ideal). This allows for the perceived equity/inequity of the overarching system to be incorporated into partner’s evaluations of their relationship.

Just as equanimity is one of the great keys to leadership and self-mastery, so, too, is equity one of the great keys to partnership and relationship mastery. So whether you are poised from within or poised from without, equanimity and equity are virtuous and wise to maintain within you and the relationships around you.