Each December, the art world converges on Miami and Miami Beach, two locations separated by scenic Biscayne Bay, but often simply dubbed “Miami,” for a myriad of art fairs and events.

The main attraction is Art Basel Miami Beach, the United State’s leading art fair. Now in its eleventh year, “Basel” as it’s called by the culturati, has secured Miami’s status as a hotspot for million dollar art collectors.

The term “Basel” is used interchangeably to refer to three leading modern and contemporary art fairs. The original, created by gallerists in 1970, is held annually in Basel, Switzerland. Miami Beach is the second and was launched in 2002. It should have launched in 2001, but organizers delayed its debut after 9/11. The third Basel premieres in May in Hong Kong. Their parent is MCH Group, a Swiss producer of tradeshows.

The story of Art Basel in Miami began thirteen years ago with an elite cadre of local collectors who made annual art-buying pilgrimages to Basel. They included Norman and Irma Braman, Carlos and Rosa de la Cruz, Don and Mera Rubell, Dennis and Debra Scholl, Martin Z. Margulies and Ella Fontanals-Cisneros. The Bramans initially pushed for Art Basel to come to the U.S.

“We’d been attending in Basel and had a close relationship with the director,” Norman Braman explains. “So, we kept asking him why not have a second fair six months after the June fair in the winter in Miami?”

The collectors and city officials – calculating Basel’s impact on the local economy – fervently wooed the fair. They also offered the perfect location in the Miami Beach Convention Center. As Bob Goodman, the Florida representative for Art Basel, explains, “It was appealing because it was close to so many hotels and the beach.”

The organizers recognized that the collectors had already infused Miami with world-class art. Don and Mera Rubell had opened the Rubell Collection in 1993. Martin Z. Margulies opened The Margulies Collection at the Warehouse in 1999. After Basel began, the others followed suit. The Scholls opened World Class Boxing; the Cisneros’s launched the CIFO Foundation and the de la Cruz Collection opened. The Bramans’ collection remains private, but they open it during Basel for art world visitors and fundraisers.

Basel and Miami were a match made in heaven for economic and demographic reasons, too. “They entered Miami at the right moment,” says Noah Horowitz, managing director of The Armory Show, as well as an expert on the international art market and the author of Art of the Deal: Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market. He adds, “The art world was beginning to bubble and it was seen as the gateway to the Latin American market.”

According to Carol Damian, director and chief curator of the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, and an expert in Latin American art, “We had a mix of cultures entering Miami from South and Central America at such a rapid pace and transforming the city into something quite remarkable. These were very wealthy, cultured and sophisticated people fleeing from countries like Venezuela and Cuba that brought with them a strong sense of community. Art Basel saw that.” This influx of wealth gave Miami great purchasing power, and modern and contemporary art is now big business. A study released in March by TEFAF Maastricht, The International Art Market in 2011: Observations on the Art Trade over 25 Years, revealed that these sectors now account for nearly 70 percent of the fine art market. Basel concentrates that billion-dollar global buying power in Miami for four days. Dealers bring work by top artists and it sells quickly. The atmosphere is competitive, mostly friendly, at times cutthroat.

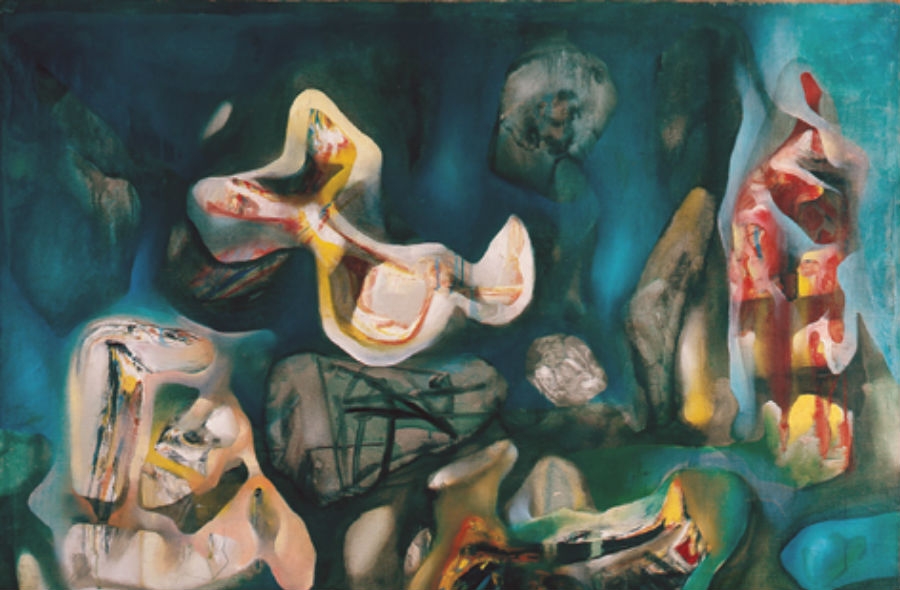

Sales transactions are confidential, so there’s no way to accurately measure Basel’s bottom line. Prices start in the hundreds of thousands and escalate to the millions. Ron Warren of New York’s Mary Boone Gallery says, “Art Basel Miami Beach is the only fair we do and we’ve always made a profit.” He adds, “This year we’re emphasizing artists that have museum shows – Ai Weiwei, Eric Fischl, David Salle and Barbara Kruger. We reinforce their visibility by showing them at Art Basel.”

Basel galleries are globally-recognized brands, but the fair positions them directly in front of new clients. As Warren points out, “It provides a global audience. There are a lot of people that don’t come to New York.”

According to Horowitz, “Fairs play an important role in how galleries plan their annual events and are an important complement to the overall gallery program. A gallery can reach 50,000 to 60,000 people in a short time frame, and because of the temporal aspect, there’s a strong call to action.”

Art Basel is the world’s ultimate juried art fair, so the exhibitor application process is extremely competitive. Goodman explains, “The selection committee meets for a week in April and of the over 800 applications we receive, they select approximately 250 galleries.”

Fredric Snitzer, who operates a Miami gallery that bears his name and who has served on the selection committee since the fair began, likens it to applying to the Ivy League. “This is the highest standard of measure for contemporary art galleries,” he says. “Does that mean that every single gallery is the best? No, in the same way that not every student at Yale is the best. But the committee works hard to create the best contemporary art fair in the world and competition is an important aspect.”

The exclusivity is alluring. According to Horowitz, “It’s about creating a market, creating something seductive and creating a mystique, and they do an incredible job.”

Galleries also receive incomparable media exposure. “Basel has a large international press and communications outreach. This is combined with the outreach from the best galleries in the world, all promoting the fair to their collectors, curators and journalists,” Horowitz adds.

Matt Bangser of Blum & Poe recognizes the benefit. “We come to the fair to sell art, but it’s also an invaluable opportunity to promote our artists. There are very few times throughout the year when we have so many sets of eyes on our program,” he says.

Buying begins before the fair opens to the public because – museum-like aura notwithstanding – Art Basel Miami Beach is a retail event for the one percent. Goodman states, “Our success is clearly based on the galleries’ success. If they don’t sell art, they’re not going to return. On Wednesday we allow serious collectors to come in two waves. Then we have the Vernissage.”

Snitzer clarified why this is necessary. “Collectors need to view the work and speak directly to the dealers in a less-crowded environment,” he says. “This is the calm before the storm. The general public is not buying, so when they see it doesn’t have any impact.”

Outside the previews, however, there’s Black Friday frenzy. Bangser suspects that, “Many of the people you see lined up stampeding out of the gates are just as turned on by that competitive experience as they are by the work they’re rushing to buy.” Warren remarks, “I don’t think it’s a bad thing. That competition is driven by passion.”

Collector passion has also spawned a near-daunting number of simultaneous, peripheral art fairs. The best include Art Miami, NADA, Scope and Pulse, which also attract leading emerging and established galleries. The excitement continues with celeb-studded events at museums, clubs, hotels and restaurants.

Snitzer states, “Nobody could’ve dreamt of Basel’s impact on Miami. It put us on the international art map.”