El Gran Fellove, a new documentary feature from actor and filmmaker Matt Dillon, follows the musical career of Cuban scat singer and showman Francisco Fellove and the recording of his final album. An artful series of interviews draw out rich details, revelations both bombastically big to achingly sweet and small. Archival photos and videos flush out the mise en scene of the era, supported well by Dillon’s own footage. A ravishing portrait of Fellove’s life as a struggling musician in Cuba, his eventual success in Mexico, and the contagious passion he had for performing.

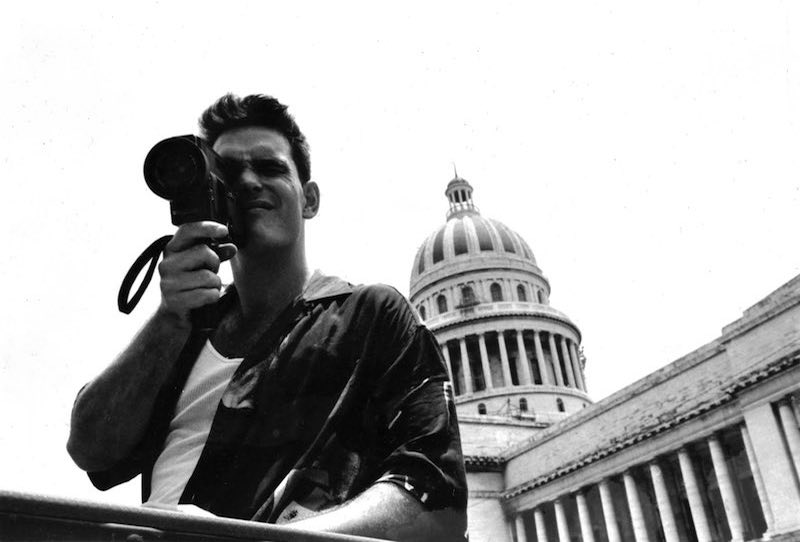

The film opens with Dillon revealing his early obsession for digging through crates of LPs, having fallen down the rabbit hole of Cuban vinyl on a 1993 trip to Havana. The genesis of the film starts in 1999, when LA bandleader impresario Joey Altruda goes looking for Fellove to float the idea of making a record with the long-lost legend. “Matt and I initially bonded as record collectors in the pre-Internet era, hunting together in all kinds of places,” recalls Altruda on our call. The two friends collaborated on the new documentary and had spent hours riffing and spinning rare Fellove. Dillon was the natural choice to come along for this wild ride. They tracked the then 77-year-old ex-pat to Mexico City, finding him remarkably sprightly. Fellove was so spry, the virtuoso proved tricky to document on film because he seemed constantly in motion.

Indeed, Joey Altruda is one of music’s best kept secrets, a musical excavator who has collaborated with aging, venerable artists to preserve culture and legacy through reinvention of music. He’s a hidden gem who has worked with enigmatic musicians of the old school generation – saxophonist Roland Alphonso (who co-created The Skatalites), guitarist Ernest Ranglin (key figure in the pioneering of Ska and Reggae music starting in the late 1950s), Plas Johnson (saxophonist of The Wrecking Crew and Pink Panther Theme), El Gran Fellove, and most recently the pioneer of Brazil’s Tropicalia movement Tom Zé.

I catch up with director Matt Dillon on a call while he’s taking a quick break from acting in a new film shooting on Vancouver Island. Dillon is more than primed to elaborate on the project he started more than two decades ago. “It was an incredibly personal experience, as Fellove had loomed so large in my imagination,” he begins. “Then you meet him and he ends up becoming larger than life, you see his humanity. You start to look at your own life, reflecting on the moments that made the difference. He was escaping difficulties with racism and the frustration of struggling as an artist. He had immediate success in Mexico; the act of expatriation was a catalyst, he was met with open arms by both the local music scene and an enthusiastic audience. Mexico City was a pivotal bridge for these artists, and I like how our film reveals this, bringing this aspect of history to light.”

Sure, Fellove hadn’t recorded for 20 years, but the temptation of these young, fresh, energetic creatives chomping at the bit to jam in his orbit proved too delicious to resist. He took the bait of a studio session. “We held a casual jam session with Fellove and the musicians on the album in someone’s home as a way to get musically acquainted and find our groove as a rhythm section. This was my first musical encounter with Fellove and it was mind-blowing, especially one particular moment when he was practically speaking in musical tongues,” Altruda recalls vividly. “It was literal and visible what he did at that moment with his tongue. I thought I had imagined it at first but afterward my friend Nicole said, ‘Did you see that crazy thing he did with his tongue?!’ It’s hard to articulate but it was almost snakelike and the sound that came forth was like nothing I’d ever heard before.”

Such sessions run throughout the film, swelling with sonic euphoria and robust collaborative energy. The scat singing veteran seemed to thrive on being “rediscovered” by this next generation. As a director, Dillon seems more interested in the psychological portraiture of a musician who left his native Cuba in the 1950s, to later reinvent himself in Mexico as an idiosyncratic vocal stylist. “What I learned in making this film is that when you lead with emotion, this is your most meaningful compass,” Dillon reveals. “Emotion first, information second. Once you can connect with the people you are featuring as subjects, the audience can connect with them and absorb information in a gratifying way because they are emotionally invested.”

Fascinated by Altruda’s memories of that time, I ask what is it about Fellove’s soulful vocals that stir such seismic, visceral emotions in him. “He sings truth, no matter what style he’s doing,” he replies. “You really hear it in his Boleros; you can feel it deep down in the gut.” No stranger to recording with “the greats”, Altruda put his whole heart into the jams. Over 35 years, Altruda has worked with the likes of Seu Jorge, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Bo Diddley, Tom Waits, and Joe Strummer just to start. This provocative chronicle of exile and full-circle reunion will be irresistible to Afro-Cuban aficionados and Latin scat fans. An irrepressible character when it comes to stage work, the period footage of Fellove in his 1950s prime gives us a rare glimpse into this full-on showman in all his glory.

Dillon recalls the sessions much the same way, saying, “Fellove taught me by example, watching him was what was beautiful. The freedom, and effortless way he would create lasting moments in front of audiences and in studio. When he was at his best was when he didn’t try.” Dillon was most struck by Fellove’s natural gift of expression. Revisiting his own emergence as an artist he reflects, “I came up as an actor at a very young age, and what we valued was that elusive Fellove factor— absolute spontaneity. The most coveted element of performance for an actor is the freedom to improvise. Recognizing this in Fellove was no different for me than recognizing it in someone like Marlon Brando or James Dean. Those actors influenced me as I honed my approach to the creative process. Fellove had it in spades when it came to music.”